Mother Tongue

We hear it before we are born. Before the first air rushes into our tiny lungs, before the first light refracts into our blinking, baby eyes, our mother tongue is already resident, dreamlike in our waiting minds.

In America, the mother tongue for most of us is English. But for millions of us baby Americans, those comforting vibrations our mothers pour over us have other names, like Spanish or Portuguese or Mandarin.

Bilingual mothers have a choice to make. Sometimes they chose their own mother tongue to speak to their babies. Other times they chose their adopted language. And sometimes, looking back, they wish they had done things differently.

Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes

Or on SoundCloud, by clicking here: Episode 4 – Mother Tongue

America the Bilingual is a storytelling podcast for Americans who are learning their next language, or would like to start. Subscribe on iTunes or wherever you listen to podcasts and hear a new episode every two weeks. (If you use Twitter, I’ll let you know about future episodes there as well.)

A Major League Language You May Not Have Heard Of

Tagalog is a sleeper among languages in America. Many of us don’t even know its name, although we have heard of the Philippines. So we are surprised when we learn that more Americans speak Tagalog at home than speak French or German or Italian. In fact, only English, Spanish and Mandarin speakers are more numerous here under the Stars and Stripes. One reason Tagalog is a sleeper is that most ethnic Filipinos speak English well. And those English skills exist partly because America and the Philippines have a special relationship, forged in the fires of World War II.

When General Douglas MacArthur said, “I shall return,” it was the Philippians he was talking about. He escaped in the night on a PT boat hellbent for Australia before the Japanese war tsunami hit with full force. The Filipinos stayed. They fought, they died, they survived. And with Americans as their brothers in arms, the Filipinos eventually won back their islands so that MacArthur could wade back ashore under his floppy hat.

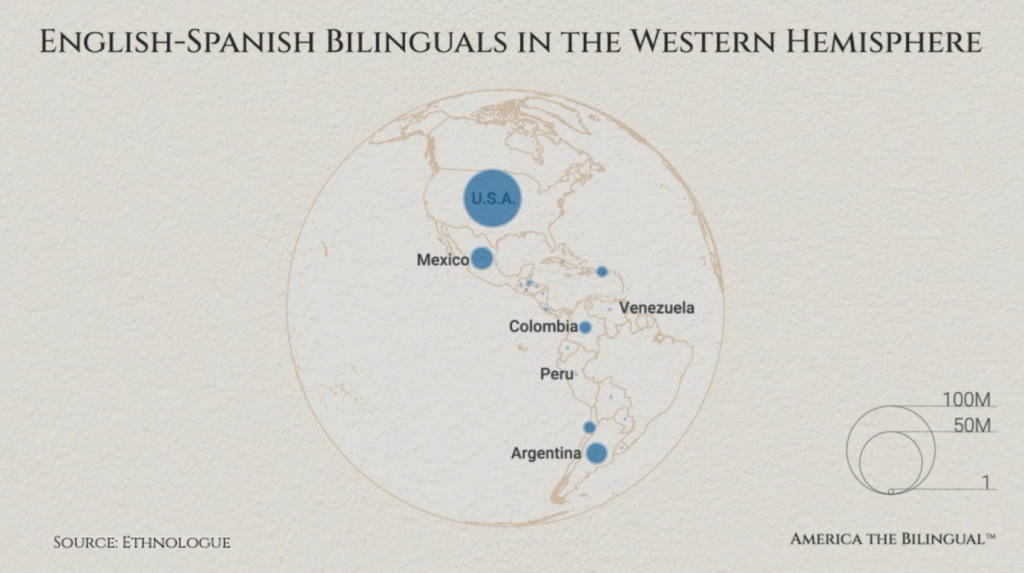

Twenty years after the war, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. Along with opening ourselves to civil rights, women’s rights, and clean air rights, in the 1960s we opened ourselves to new kinds of immigrants. Fewer came from Europe and more came from the east — from the Philippines, from Korea, Vietnam, and China. More came from the south, too — from Cuba, Argentina, Venezuela, Mexico and Brazil.

This third great wave of American immigration may now be coming to an end. But today the United States has some 1.6 million people who speak Tagalog at home. Some of them are mothers. Those mothers choose what to speak to their babies and thus help steer the bilingualism — or monolingualism — of the tiny Americans in their arms.

Credits

A shout out to America’s language teachers. The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (I love their acronym ACT-Full) and its Lead with Languages campaign encourages bilingualism for all.

This episode was written by me, Steve Leveen, and our producer Fernando Hernández who also does sound design and mixing. Our editorial consultants are Maja Thomas and Mim Harrison, research assistance from Stanford undergraduate Alma Flores-Perez.

Graphic Arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio.

Music in this episode by Kevin Macleod, Andy G. Cohen, Nuno Adelaida, and Captive Portal. All thanks to the Free Music Archive directed by WFMU. Additional music courtesy of Francisco Penilla.

Music and sounds in this episode by:

Zulmira by Nuno Adelaida, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License.

Feeling like a Delicate Cookie by Captive Portal, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike License.

Bumbler by Andy G. Cohen, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.

Beach Party by Kevin Macleod, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.Changes include high pass EQ Filter.

Quasi Motion by Kevin Macleod, teleased under a Creative Commons Attribution License.

Chicle Bombita by Francisco Penilla, courtesy of the author, whose work can be found at @francisco-penilla.

Kids Garden Hose by klankbeeld, licensed under the Attribution License.

Children City Payground by soundbyladyv, licensed under the sampling + License.

Landing in Lisbon by mollymolata, is Licensed under the Attribution License.

My favorite reading on American Immigration and our Lost Languages

For a delightful little book on American immigration, I recommend American Immigration: A very short introduction, by David Gerber. Learn how what seems new in today’s immigration debates really isn’t. (Today’s immigrants are never as good as yesterday’s.)

Gerber leads us expertly through the three great waves of American immigration. He packs it all into 160 pages in one of these little gems that fit so well in your hands and pocket from Oxford University Press. (Spend an evening reading this before stepping onto one of those restored ferries that will take you over to the museum at Ellis Island.)

I’m indebted to Stanford’s luminary professor of history, David M. Kennedy, for sharing with me over a glass of wine a few of his favorite books on American immigration and here share them with you: Uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations that Made the American People by Oscar Handlin, and Becoming American: An Ethnic History by Thomas J. Archdeacon. And don’t miss Kennedy’s own 1996 article in Atlantic Monthly, “Can We Still Afford to Be a Nation of Immigrants?” Twenty-one years old, fresh as ever.

For a history of language politics in the US, I was blown away by Kenji Hakuta’s 1986 book The Mirror of Language: The Debate on Bilingualism. Hakuta explains in his clear, gentle prose, how half-baked science misinformed generations of Americans about the supposed disadvantages of bilingualism. Hakuta is Emeritus Professor at Stanford. I am grateful to him for sharing his wise perspectives on the language teaching history in our country.

For statistics on languages spoken at home in America, see the US Census American Community Survey Reports.

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment