Photo by Chris Macke

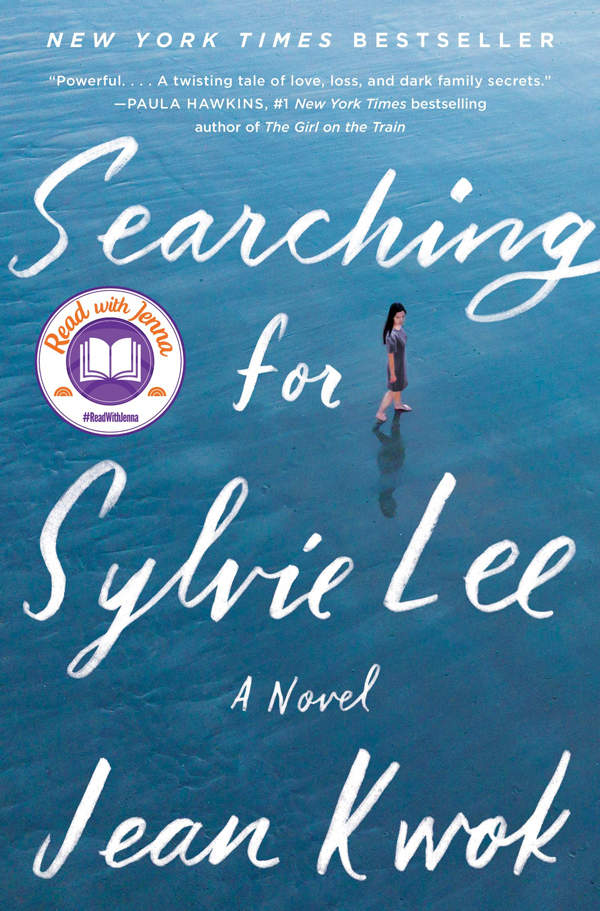

Since her debut novel, Girl in Translation (which was translated into 16 languages), Jean Kwok has earned the coveted status of international bestselling author. Her newest work, Searching for Sylvie Lee, is a Today Show Book Club pick and earned Jean another spot on the New York Times bestseller list. It comes with a list of encomiums as long as a kite string: O Magazine, Buzzfeed, the Washington Post, CNN, Time, Newsweek, and more.

Language plays a key role in all of Jean’s fiction, and together with reading, it has been central to Jean’s own extraordinary story, which we share with you below.

It’s hard to say which was worse, the cockroaches or the cold. The roaches penetrated everything, even open tubes of toothpaste. Jean had to shake out her sweater every morning, a task made more fraught by the fact that it was her only one.

But the cold pierced with equal insidiousness, right through her small, five-year-old frame. Jean and her older siblings and their parents found relief only near the kitchen stove, the single source of heat in the derelict apartment where they lived in Brooklyn. Her parents left the oven door open all through the winter, a somewhat Sisyphean arrangement since the window in the kitchen had no glass, just a garbage bag tacked to it.

Then, every day when Jean and her family crossed the bridge into Manhattan, came the shift to searing heat. The factory where she and her brother went to work after school —de facto daycare for her parents, both toiling excruciatingly long hours to pay off the immigration fees—was aptly called a sweatshop. The steamed garments that Jean had to carry tinted the dust that clung to her arms the colors of the fabrics.

Jean told no one in her school about working in the factory—at first, because she couldn’t. Her family had left their comfortable home in Hong Kong, with a nanny and heat, to come to the United States, and none of them spoke English.

A few years later, though, when Jean was proficient in this new and foreign tongue, she told her best friend at school about the factory. When her friend’s father heard the story, he assured his daughter that Jean was making it up. After all, he said, there was no child labor in factories in America.

Ah, but there was.

A very young Jean, before coming to America

Lifting the fog on a new language

Jean’s story follows the trajectory that many immigrants’ stories have for much of America’s history. After a painful, punishing beginning, her parents finally paid off their immigration fees, and the family moved to a brownstone in Brooklyn Heights. And while the parents never mastered English, the children did.

Sometimes it was like being on different ends of that bridge between Manhattan and Brooklyn, the parents speaking only Chinese, and the children toggling between Chinese and English.

Not that learning English was easy, even for a five-year-old.

“When I first came to the U.S. and people started speaking to me in English, I felt like I was lost in a fog,” Jean recalls. “Sometimes I’d be able to make out the shape of their words but most of the time, all I could perceive was a bewildering jumble of sound. The worst,” she added, “was that I was still expected to respond when I had no idea what had been said.”

Jean has a meal in her new home, the U.S.

It took about a year before the fog started to lift. Still, although she could keep up with what the teacher was saying in her classroom, she could not keep pace with her classmates’ progress.

Her older brother gave her a diary—a prized possession for a seven-year-old who had so few of them. “Whatever you write in this diary, that belongs to you,” he told her.

Jean wrote in her diary faithfully, in English rather than Chinese. “I knew I needed to practice English as much as possible,” she says. Besides, her Chinese was starting to lapse. “Like many other immigrants, my parents were most worried about my English language acquisition skills and encouraged me to forget about Chinese, which was truly a pity,” she says.

Even though Jean says that “there was not a single moment when I felt like I had mastered English,” she came to excel in it, capturing the championship in her school’s spelling bee when she was eleven.

Reading helped. “I used to take out the maximum number of books from the public library every week when I was learning English,” she says.

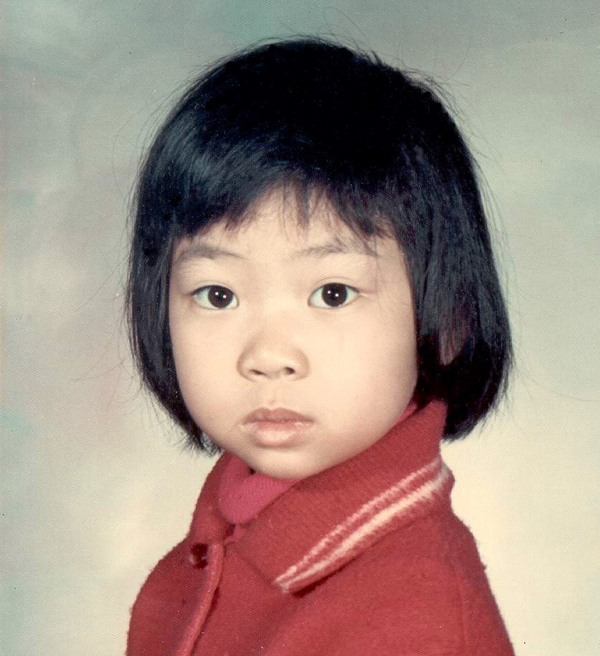

Jean at five years old, when she first heard English. “I felt like I was lost in a fog,” she says.

Poetry in Latin, mambo in Spanish

When Jean was accepted into Hunter College High School, a public school in Manhattan for gifted students, one of the requirements was learning another language. Jean picked Latin, figuring it would help her with her English vocabulary.

“On the first day of class, our Latin teacher asked us, ‘Why did you pick a dead language?’ I thought, ‘It’s dead?’ I’d had no idea. But I grew to love Latin. I won the Latin scholarship when I graduated from high school and read Latin lyric poetry at Harvard as well.”

She put herself through Harvard working four jobs, one of them teaching English. Harvard was where Jean realized that she could pursue her dream of becoming a writer, so her MFA from Columbia came next.

But before she started her master’s, she danced—professional ballroom dancing, something she had long wanted to do (that, and grow her hair, despite her mother’s objections).

“My professional dance partner was from the Dominican Republic,” Jean says. “We used to go up to Washington Heights and do mambo at Dominican parties. I probably learned more Spanish from him than from the ballroom dance syllabus.”

Then on a backpacking trip to Honduras, she fell in love with the man she would marry. He was neither Latino nor Anglo nor Chinese. He was Dutch.

“I knew from my first immigration experience that learning the language was absolutely the most important thing I needed to do if I was going to try living in the Netherlands with him,” Jean says.

Jean with her school principal and her trophy—she won her school’s spelling bee when she was eleven.

Reading in two languages…

This learning curve was not as steep as the first, even though Jean was now in her twenties, past the golden age of internalizing another language. Luckily for Jean, English and Dutch had more in common than either did with Chinese. Once in the Netherlands, she took an intensive course in Dutch at Leiden University, where she was once more teaching English.

Here again, reading played a central role.

“Reading has been absolutely crucial to my learning any language,” Jean explains. “When I teach, I tell my students to read something they truly enjoy. Even if they love reading car magazines, if they read regularly, their language skills will improve tremendously.”

Perhaps the most telling sign that Jean loves to read is how she has increased her vocabulary the way that many of us have at some point in our reading lives. “Even now,” Jeans says, “I often come across words in both English and Dutch that I don’t know how to pronounce because I’ve never heard them spoken. But those words are a part of my vocabulary thanks to reading.”

She tends to read different kinds of books in her two main languages—novels and poetry in English, which she now considers her primary language, and nonfiction in Dutch.

Speaking in two languages…

Jean and her husband are raising their two sons, in the Netherlands, to be bilingual. Both parents speak the language they’re stronger in—English for Jean, Dutch for her husband.

That way, Jean says, their boys are “only hearing the most fluent version of each language.”

In their own conversations, she and her husband switch back and forth, depending on the topic. And, Jean adds, “if we get very intense about a subject, I’ll speak English and he’ll speak Dutch and we won’t even notice that we’re not using the same language!”

…but thinking and feeling in three

On any given day, Jean says she thinks in all three of her best-known languages. She points out that “there are certain words that I know best in one language because of my personal experiences.”

She’s likely to think about mortgages in Dutch, because she became a homeowner for the first time in the Netherlands. Publishing-related matters call for English. And math summons Chinese, the language in which she learned multiplication.

Chinese is also the language of comfort for Jean, inextricably bound up with childhood, when we most seek it. English, her coming-of-age language, is for “love, art and ideas.” When practicality is called for, Dutch marches into her head.

But sometimes, Jean says, “I’m not even sure if I’m speaking English, Chinese or Dutch. The words just come out of my mouth in whichever language is needed.”

Helping her readers experience the story through language

All three of Jean’s novels—Girl in Translation (2010), Mambo in Chinatown (2014), and Searching for Sylvie Lee (2019)—reach into Jean’s story for theirs.

Jean has a particular, and particularly effective, way of placing readers in the story: by placing them in the language of the protagonists.

In Girl in Translation, to give readers a sense of what it’s like to be an immigrant, when the heroine doesn’t understand what someone is saying to her, neither do you as the reader.

“The heroine hears, ‘You a hero’ when the teacher had actually said, ‘You got a zero,’” Jean explains.

In Searching for Sylvie Lee, three women tell the story, each one filtering it through her native tongue—Chinese, Dutch, English.

“The reader first sees Chinese-speaking Ma through her English-speaking daughter’s eyes as a very simple woman who can barely manage broken English,” says Jean. “But when we enter Ma’s chapter, where Ma is thinking in Chinese, we realize that Ma is a wise, complex, passionate woman—a person her own daughter barely knows because of the language barrier in between them.”

Jean once told an interviewer, “I hope to put the reader on the other side of the curtain of language so that maybe someone who’s a native speaker of English learns what it’s like not to be a native speaker of English.”

Not only do we learn what it’s like; we live what it’s like, emerging from the story with a newfound empathy. In any language.

– Mim Harrison

13 January 2020

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment