When President John F. Kennedy traveled to West Berlin on June 26, 1963, he wanted to assure the people there—who were literally walled off from the eastern portion of their city by Communist Russia—that Americans stood with them. Ever the classicist, Kennedy drew from the ancient Romans’ statement of Civis Romanus sum “I am a citizen of Rome.” He wanted to convey that same spirit, but in German:Ich bin ein Berliner.

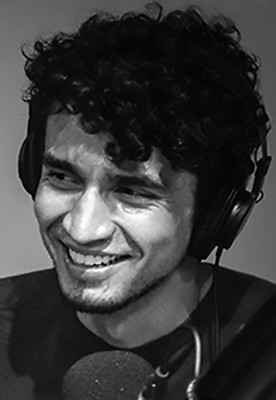

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy speaks—in Spanish—to leaders of the 2506 Cuban Invasion Brigade at the Orange Bowl in Miami, Florida, where she delivered her speech—in Spanish—on December 29, 1962. Photo: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

But Kennedy, despite his quick mind and extensive world travel, was no linguist. So he had someone write it down phonetically, to ensure he pronounced it properly.

Had it been his wife speaking that day, that would not have been necessary.

When it came to languages, JFK and his wife, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, could not have been more different. From when she was a child, Jackie loved languages, French in particular. An ardent Francophile, she named her poodle Gaullie, after France’s Charles de Gaulle, whom she later met as First Lady. Her year of study at the Sorbonne in Paris when she was in college cemented her command of the French language.

Among the iconic moments of JFK’s presidency was the trip he and the First Lady took to Paris in 1961. Jackie was in her cultural and linguistic element. Her husband clearly was not. But his wit was as sharp as ever—he famously introduced himself at an official function as, “I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.”

Finding her campaign voice—in French, then Spanish

As a Congressman from Massachusetts in the 1950s, Kennedy needed to be conversant in the politics of Southeast Asia, where the French then had a presence. Jackie, not yet his wife, translated the French research books for him.

For Jackie, her affinity for other languages helped to transform her from a reticent campaign wife to a connector. She made her first campaign speech for Jack Kennedy, then up for re-election to the U.S. Senate, in 1958. And it was not in English: it was in French, to the members of the Worcester Cercle Francais, in Worcester, Mass.

Her comment following the speech is a testament to the power of bilingualism. Delivering the speech in French was, she said, “not as frightening as it would have been in English.” (Bilingualism as a cure for shyness? It just might be so.)

The Worcester speech was the start of what became a potent arrow in the quiver of Kennedy’s presidential campaign two years later. In Milwaukee, Jackie spoke to the mostly Polish-descent audience in Polish, telling them in their heritage language that “Poland will live forever.” In New Orleans, she spoke in Cajun.

Jackie was a polyglot, speaking also some German and Italian—and speaking Spanish fluently. She taped radio ads in French, Italian and Spanish, urging the listeners to vote for her husband. She also taped a TV ad, in Spanish.

As the campaign entered its final, uncertain stretch, Jackie spoke to New York City’s Puerto Rican and Dominican constituents in their first language. Kennedy needed New York, and he took it. Jackie’s take on her multilingual campaign efforts weren’t quite so political: “All these people have contributed so much to our country’s culture; it seems a proper courtesy to address them in their own tongue,” she wrote in “Campaign Wife,” her syndicated newspaper column (the closest thing in its day to social media).

This is also where she wrote, “I am grateful to my parents for the effort they made to teach us foreign languages.”

Later, as First Lady, she reminded a French reporter—in French—that “I’m very interested in the foreign students. I was one myself.”

“That other language doubled my life”

Jackie also made a decision on how, linguistically, she would raise her children. In her oral-history interview with the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., she said, “I’d always had this mania before about making my children learn French because I saw how that other language absolutely doubled my life, and made you able to meet all those people…but I said ‘I’m going to make my children learn Spanish as their second language.’…[Because] really, we should turn to this hemisphere.”

When she accompanied JFK to both Mexico and Venezuela in 1962, she spoke to the crowds in Spanish. In the waning day of December that year, Jackie also addressed a huge crowd in Miami, Florida’s Orange Bowl, speaking only in Spanish to the Cuban exiles who had been part of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba the year before.

On November 21, 1963, JFK was in Houston with Jackie, speaking to the League of United Latin American Citizens. In a sequence now well-honed between the couple, JFK said to the audience, “In order that my words will be even clearer, I’m going to ask my wife to say a few words to you also.” Jackie’s words were, of course, in Spanish.

That speech became the last public words of this American president and his first lady—spoken not in one language, but two.

– Mim Harrison

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Both are sorely missed … in spite of his escapades.

His escapades? Were you witness to them? Let a dynamic, activist, freedom fighter President be remembered for a exactly that!

Bravo!!

Jackie Kennedy knew just about every foreign language that is spoken in Europe.

Mrs. Kennedy also had a few affairs during her marriage to JFK.

I always admired her. One of my favorite suits was a knock off of her Chanel suit I wore in the 60’s. I remember my date called me Jackie all night . What I would do to have them back in the White House again!!!