28. And Crown Thy Good with Brotherhood

“We have ground rules,” said Amjad, an Arab American speaking about his family of five, “and the ground rules say in public places we don’t speak a word of Arabic.”

Freedom of speech is a constitutional right we take for granted in America, yet many bilingual speakers avoid speaking their non-English language in public for fear of hostile looks—and worse. Are we destined to perpetuate this contradiction, or might America be ready to move on? In Episode 28, hear Amjad’s story and what happened when his family violated their ground rules.

Some 65 million Americans speak a language other than English at home, yet many are afraid to speak it in public.

According to U.S. Census figures, approximately 65 million Americans over the age of five speak a language other than English at home, including 1.2 million Arabic speakers. Should they feel free to speak their non-English language outside their homes?

Amjad, who preferred we didn’t use his last name, is a citizen of the United States and of Jordan. I interviewed him shortly after this incident in New York City went viral:

A customer in a restaurant began berating employees for speaking Spanish. “This is America!” he yelled. Accusing them of being illegal aliens, he pulled out his phone and threatened to call ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement). The video of his tirade went viral on Facebook and was picked up by TV news programs.

The fact that his outburst made news is testament to the fact that most people find his behavior outlandish and objectionable. Yet while public outbursts like this one are unusual, they do reflect widely shared beliefs that speaking languages other than English in public is somehow un-American. And they are what immigrants like Amjad are afraid of.

Racism and tough love

Our history, like many other countries’ and cultures’, is full of examples of language suppression, both by social norms and bylaws. Native Americans were punished for speaking their ancestral languages at school, including the Navajo boys who later were asked to join the Army and use their language in code to help defeat the Japanese in World War II. (They did exactly that, and were later decorated as heroes.)

Earlier in the 20th century, some German Americans, our nation’s largest ethnic group, were lynched or incarcerated for speaking German, as the country fought against Germany in World War I. During this period, many school districts abolished the teaching of German, and some cities passed laws making the speaking of German in public or on the telephone illegal. The rest of the 20th century saw many immigrant children punished for speaking their home language at school.

While some of these actions can be chalked up to racism, others can be attributed to tough love. Many believed it was best for our children and our nation that the languages of the old country be left in the old country. What the nation needed was Americans of undivided loyalties, Americans without accents. And what students needed was English—and only English—in order to become fully educated.

English Only

Advocates for English monolingualism, then and now, justify their position by citing the benefits to national unity of sharing a common language and the sufficiency of English for a practical education.

In my opinion, they are largely correct.

Developing a common language did, and still does, bring Americans of diverse backgrounds together. In the main, we can communicate with one another, and that is of incalculable value. The vast majority of Americans can read our laws and our Constitution. As for a practical education, you can not only graduate from college, but can earn a Ph.D. or any number of other advanced degrees being an English monolingual. You can become a U. S. Senator, a Chief Justice of the United States or even President without knowing one word of another language.

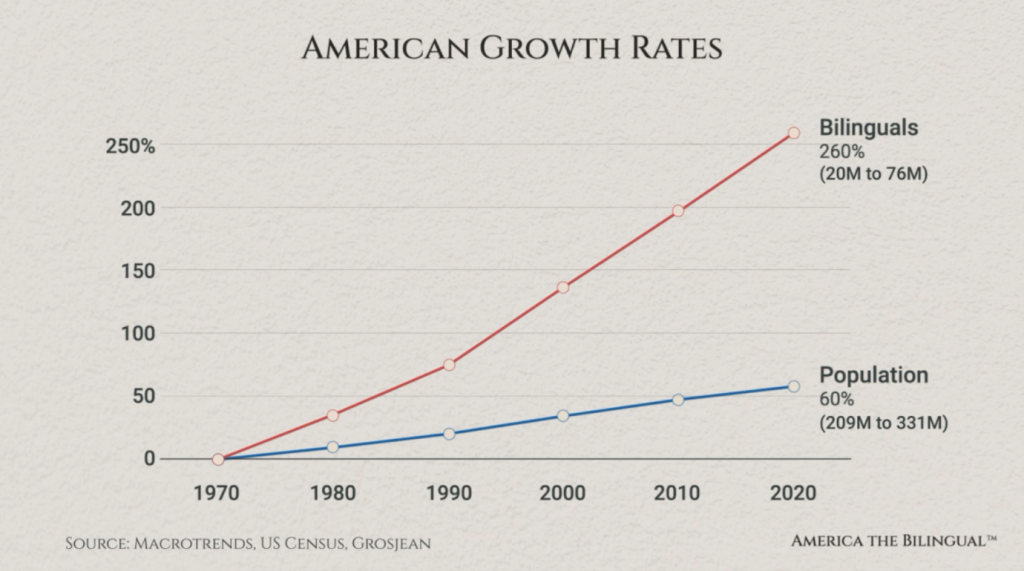

The battle for the widespread adoption of English in America was won long ago. It is now time to set our goals higher. The goal for our last century was universal English literacy. The goal for our present century should be universal bilingualism.

New social norms for a new language reality

Now we know that bilingualism is correlated with better academic performance in general, including in English. Now we know that bilingualism is correlated with mental health benefits as well as job opportunities. Parents are increasingly demanding bilingual education for their children, witnessed in the rapid rise of dual-language schools across the nation.

As for our national defense, what the country needs is more bilinguals, not fewer. This is why the Department of Defense funds summer language camps for students studying “critical-need foreign languages,” including Arabic.

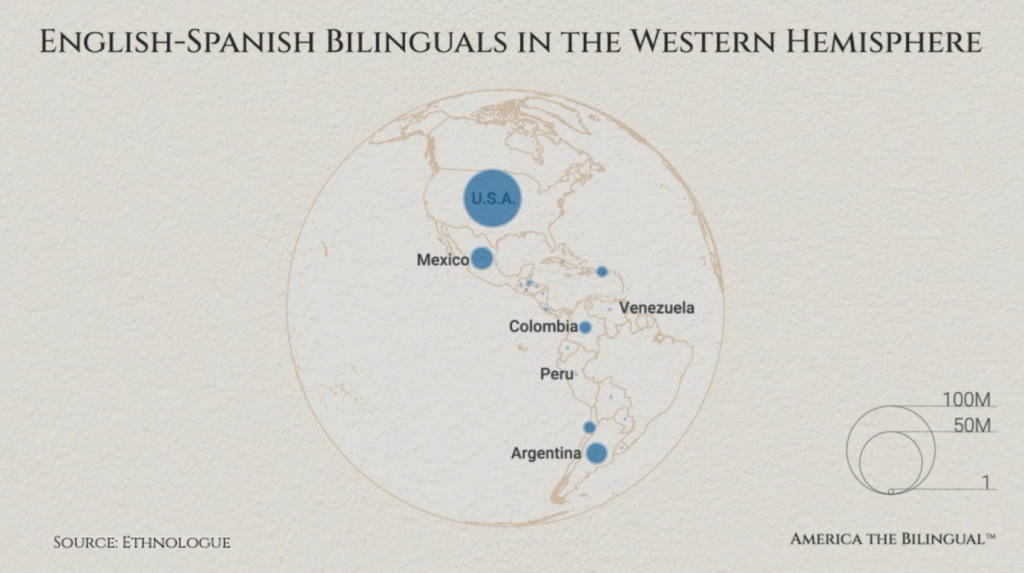

Speaking another language in public is not displaying divided loyalties but American strength. When we hear Americans speaking Russian or Chinese or Spanish, we are hearing American linguistic capital that is used in all number of ways to advance our national interest (much the way financial capital does). It helps us sell American goods overseas, and buy international goods at better prices and of higher quality. It builds relationships with people around the world, as we can understand non-Americans better, thus building American soft power in myriad ways. American linguistic capital helps us keep our borders secure and our nation safe from terrorists. This is why the Border Patrol employs bilinguals and why the Department of Defense funds language learning.

It’s time for an adjustment in our social norms regarding language use. Instead of frowning on people speaking a “foreign” language, we ought to smile at them. In fact, we ought to catch people in the act of speaking a non-English language in order to compliment them. We might ask them what they are speaking (in English, of course) and tell them it sounds beautiful. Or we might thank them for representing our country as bilinguals.

Today’s American bilinguals are firefighters, police, nurses and teachers. They are business people, mayors and members of our Armed Forces. We should thank them all for their service, and for being part of that brotherhood—and sisterhood—that we sing of in “America the Beautiful.”

We’re not there yet.

Bumper stickers for sale on Amazon reflect the past

Search on Amazon and you can buy bumper stickers that say, “Welcome to America, Now Speak English!!!” and plenty of other versions of the same idea that are less polite.

What I couldn’t find on Amazon was the bumper sticker popular among language teachers: “Monolingualism is the Illiteracy of the 21st Century”—the quotation by language visionary Gregg Roberts.

I don’t want to deny the basic human response when hearing people speak a language you don’t understand. I remember feeling uncomfortable in an elevator once when all the people around me were speaking German, which I don’t speak. Are these people talking about me? Are they making fun of me? I recalled thinking. You may have had similar reactions.

This feeling probably goes back to some of our most basic emotions as primates and wanting to be part of a community. But just as we have evolved to recognize and moderate our reactions in other realms, it’s time for us to evolve as a nation to the widespread praise for bilingualism and to see it for the nation-building and human-building practice that it is.

When you hear people complaining about “today’s immigrants,” keep in mind that it is the perennial complaint about immigrants throughout history, and not just in America but in other countries, too. It’s what Professor Kim Potowski calls the “Grandparent Myth.”

Raise a flag for bilingualism

The facts in America say that today’s immigrants are learning English faster than our grandparents did, which indeed they must in order to advance in today’s world. The problem is not their lack of English, but rather their rapid abandonment of their heritage languages, which is precisely the goal of heritage language instruction and dual-language schools.

When we hear a language other than English in public, rather than thinking divided loyalties, think multiple loyalties. It’s a common sight in our country to see a flagpole with the American flag on top of a state flag below. This is not divided loyalties but multiple loyalties. The fact that a Texan is proud to be a Texan doesn’t make her less of an American. An American who is proud of his Italian heritage is no less of an American.

The antidote to the Amazon bumper sticker

This is one of a dozen or so “Speak English!” bumper stickers available on Amazon today. (My system is set to Spanish.)

Here’s an America the Bilingual alternative:

HEAR THE STORY

Hear more of the story in Episode 28 of the America the Bilingual podcast, “And Crown Thy Good with Brotherhood.” Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes. Or on SoundCloud here. I’ll let you know about future episodes on Twitter as well.

Sources, Credits and Additional Thanks

The America the Bilingual podcast is part of the Lead with Languages campaign of ACTFL — The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

This episode was written by me, Steve Leveen. Our producer is Fernando Hernández, who also does our sound design and mixing, and our associate producer is Beckie Rankin. Our brand and editorial director is Mim Harrison. Graphic arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio.

Support for the America the Bilingual project comes from the Levenger Foundation.

Music in this episode, “Quasi Motion” by Kevin MacLeod, was used with a Creative Commons Attribution License. Our thanks to Epidemic Sound for helping us make beautiful music together.

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment