“Steve Leveen shows how we can step up our own personal development while at the same time take a deeper responsibility for our nation’s role in the world.”

“Steve Leveen shows how we can step up our own personal development while at the same time take a deeper responsibility for our nation’s role in the world.”

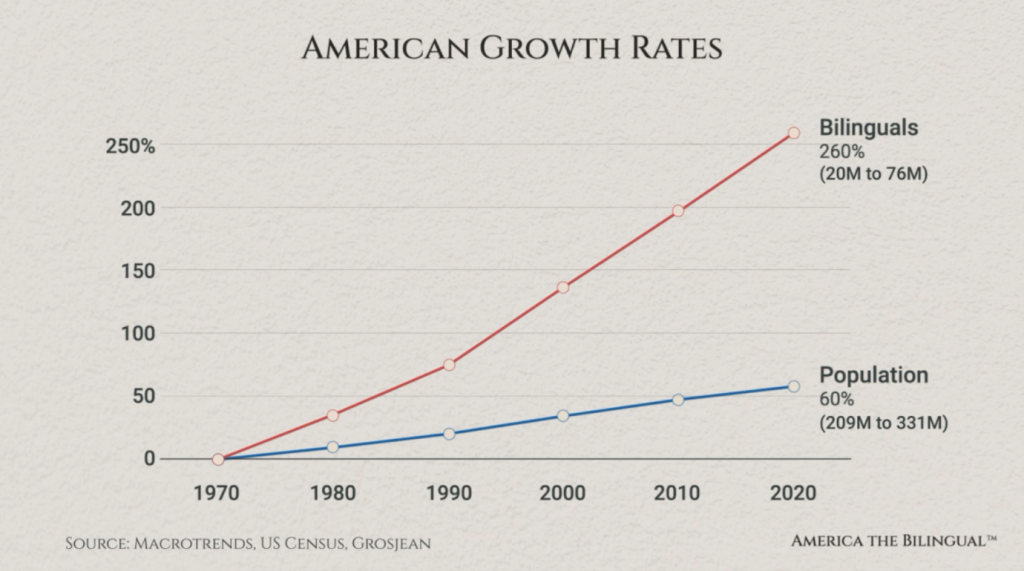

In the United States, we have 76 million people who speak a language other than English at home.

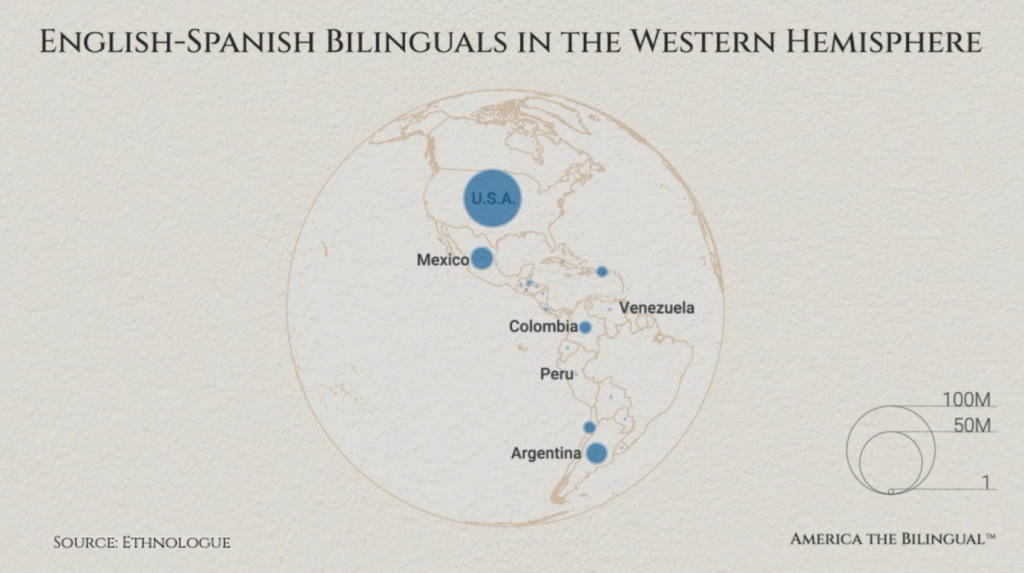

Most of these people also speak English well and thus are bilingual. In addition to having some 40 million Spanish speakers and 2.5 million Chinese speakers, we have at least 250,000 speakers of 30 different world languages. No country can match America in terms of our numbers of people who speak the world’s most commonly spoken languages. We view the linguistic skills of bilingual Americans as our nation’s linguistic capital, a subset of our human capital.

It enhances peace within our borders and projects soft power beyond our borders. International linguistic capital is something to be prized, preserved, and built upon.

Hear from a champion of American bilingualism on

why America’s bilingual century has arrived…

what it means for present and future generations…and

how you can be part of it

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

— Karen Decker, President, International Center for Language Studies and the Association of Language Companies, 2023 Annual Summit

– Nelleke Van Deusen-scholl, Former Director, Yale Center for Language Study,

Yale University Consortium for Language Teaching and Learning May 2023~~~~~

‘Excellent. Insightful. Spectacular!’

– Attendees at Steve’s presentation to the International Center for Language Studies

~~~~~

‘One of the students who attended your talk informed me this week that he wants to study abroad and pursue a minor in Spanish.’

– Giosuè Alagna, PhD, Lecturer in Spanish, Department of World Languages and Cultures, Valparaiso University

BOOK NOW

FORMAT: In-person or Virtual

FEE RANGE: $5,000-$7,500; lower negotiated rates for nonprofits.

Proceeds will fund Conversation Corps grants of the America the Bilingual Project and other designated bilingual programs.

CONTACT:

Mim Harrison, Editorial and Brand Director America the Bilingual

mimgharrison@gmail.com

(Please use subject line: “Interested in booking Steve”)

The Levenger Foundation is a private family foundation in the US whose principals include Steve Leveen, the founder of America the Bilingual, and members of the Leveen family.

“Data turned useful” is how Alli describes her work. It calls to mind the saying about how seeing is remembering. In Alli’s work, it’s also a case of seeing being the catalyst for engaging.

Provided, of course, that what you see is itself engaging.

“You want to be meeting your audience at their level of expertise and interest in your message,” Alli explains, “and using the right visualization tools to reveal patterns they would otherwise not see.”

Alli’s tools come with their own intriguing language. Tessellations. Choropleths. Bee swarms, which is what this image from her work for America’s Bilingual Century shows.

She and Steve turned a number of the facts he presents in his book, such as why Americans are more bilingual than most of us know, into a set of animated graphics like this one.

“We had to figure out how to break down the data into digestible pieces,” Alli says of the project. “There’s an entertainment factor to it—keeping it interesting but not overwhelming.”

Alli traded her former job as a data analyst at the Pentagon to venture out on her own as an information design consultant. It was, in part, the maps she created at the Pentagon that steered her in the direction of data visualization. She got a graduate certificate in geospatial intelligence and then did some projects showing spatial analysis. Soon she was hooked on data’s visual potential.

She started a podcast not as an expert but as an explorer, seeking to connect with others in her new field. Now she’s a frequent podcast guest, including for the Urban Institute.

While much data visualization is informational, it can also be instructional, as it is with Steve’s project, Alli says. Either way, she says, “it gives you a bigger sense of the world around you.”

Four years of Spanish in high school. Pre-conversational Russian by immersion: Allie’s husband is Ukrainian and speaks Russian with family members.

“I realized you don’t have to know a lot of the language to have meaningful moments. My husband’s grandparents were in their eighties when they moved from Ukraine to the U.S. His grandmother knew very little English and I knew very little Russian. But we could say ‘thank you’ and ‘I love you’ to each other in the other’s language. I had a very special relationship with his grandmother. The fact that we were both trying to say words in each other’s language was an act of love.”

4 January 2021

For information and author interviews:

Mim Harrison, Publishing Director

America the Bilingual Press

mimgharrison@gmail.com

DELRAY BEACH, FL—A new book that has already won high praise from language experts, CEOs, nonprofit leaders and two Pulitzer Prize winners invites all Americans to participate in the move toward becoming a bilingual country—even if they themselves are not bilingual.

Neither is the author.

America’s Bilingual Century: How Americans are giving the gift of bilingualism to themselves, their loved ones, and their country by Steve Leveen, who describes himself as “an emerging bilingual,” puts forward a persuasive argument for a country whose citizens speak English and another language. For some, it might be their heritage language—the language that their grandparents spoke. For others, it might be what Leveen calls their “adopted language,” one that they feel an affinity for and make a lifetime commitment to. Leveen’s adopted language is Spanish.

Says Leveen: “English is what unites us. Our other languages are what define and strengthen us.”

America’s Bilingual Century blends exhaustive research, engaging prose and endearing stories to draw readers into an idea that many Americans may not have considered.

Tapping experts in linguistics, education and the social sciences, Leveen takes a deep dive into America’s twentieth-century social history, chronicling the country’s evolving views toward bilingualism. What emerges, he says, can write a new narrative for languages in America:

“At diplomacy, at journalism, at intelligence and military operations, at humanitarian work and in business, we’re better when we’re bilingual,” Leveen says. “We’re more competitive in the marketplace, more compassionate in our dealings with others, and more successful in turning out smart kids to lead the country in whatever calling they choose.”

One of the most potent change makers are the dual language schools that are sprouting like wildflowers around the country. Educators who study students’ performance are finding compelling evidence that dual language learners emerge not only speaking two languages but also being more successful students. “These students tend to perform better in all their subjects,” Leveen reports.

Leveen devotes one section of America’s Bilingual Century to dismantling a dozen myths about Americans and bilingualism, from “I’m just not good at languages” to “Technology will make language learning obsolete” to “America’s so big, where would I ever use it?”

In another section, he offers resources for parents who are not bilingual but would like their children to be, including summer language immersion camps, study abroad opportunities and bridge years.

And in a third section, he provides how-to’s for adults hoping to become bilingual (or close to it). Among his practical suggestions: switch the language on all your electronic devices to your adopted language to give yourself a virtual, digital immersion. And an important philosophical suggestion: think about not just how you will learn the language, but where in your life that language will live.

While it’s never too early to learn another language, Leveen says it’s never too late, either.

He takes readers along on his own bilingual journey, which he began at age 53, sharing not just the breakthroughs but also the bumpy patches, with gentle humor and deft storytelling.

He tried too soon, for example, to read 100 Years of Solitude in Spanish. (“My friends stopped asking me what I was reading because my answer was always the same. Finally, I realized that this revered classic had magically transformed itself into One Hundred Years of Reading This Book.”)

And he knew he was in for a humbling experience when he took a Spanish class at Harvard with undergraduates for whom, he says, he could have been their granduncle. (The only advantage over them that he can find: “I show up on time.”)

America’s Bilingual Century is not just a how-to, but a why-to. Globally, English learners outnumber native speakers 20 to 1, Americans being the largest group of native English speakers. They have an obligation to have conversations with learners, Leveen says.

“Despite all our technology, genuine conversations are still the most important and hardest-to-find ingredient necessary for language fluency,” says Leveen.

And, he adds, in order to be the most effective and empathetic conversation partners, we Americans who are native English speakers must be language learners ourselves. To make this idea actionable, Leveen includes two appendixes in America’s Bilingual Century where he suggests an American Conversation Corps, consisting of American bilinguals and emergent bilinguals, and an American Bilingual Honor Code that corps members would follow.

Leveen spent a year as a fellow in Harvard’s Advanced Leadership Institute and another in Stanford’s Distinguished Careers Institute as part of his research for the book. His reporting took him across America to a Greek dual language school in Miami; a Cherokee school in North Carolina; and English classes for janitors at Facebook headquarters in Palo Alto. With recording equipment in tow, he visited America’s most famous language immersion camps at Middlebury College in Vermont; Concordia Language Villages in Wisconsin; and Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He also drew on dozens of podcasts with language learners and teachers that his America the Bilingual project created in partnership with ACTFL, the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

The title of Leveen’s book was inspired by Henry Luce’s famous editorial in Life magazine in early 1941, when Americans were still debating entering the war. Titled “The American Century,” Luce’s essay was a stirring call for Americans to live up to the country’s ideals of freedom and justice.

Embracing bilingualism is a way for Americans to continue those ideals in our present century. Says Leveen, “There is a larger life—both as individuals and as a nation—that awaits us when we embark on our bilingual journey.”

Steve Leveen is the founder of the America the Bilingual project, which champions bilingualism in America as a path to a stronger, healthier nation. The project welcomes not only those who are bilingual but also those who are aspiring to be. Visit www.americathebilingual.com.

In his earlier professional life, Leveen was the CEO of Levenger, the company that he and his wife founded that offers products for reading and writing. He holds a PhD in Sociology from Cornell.

Editor’s Note: Kirkus Reviews is a well-regarded book review magazine that’s been around for more than 80 years. This is the full review the magazine posted on November 4, 2020, of Steve’s America’s Bilingual Century.

TITLE INFORMATION

AMERICA’S BILINGUAL CENTURY

How Americans Are Giving the Gift of Bilingualism to Themselves, Their Loved Ones, and Their Country

Steve Leveen

America the Bilingual Press (572 pp.)

ISBN: 978-1-7339375-2-8

BOOK REVIEW

An advocate for bilingualism notes the many advantages of learning other languages.

In this nonfiction book, Leveen, the author of Holding Dear (2013), uses his own experience learning a second language in

adulthood as a starting point for exploring the value of multilingual living. He also draws on dozens of interviews with

linguistic experts and others—many of which were collected for his America the Bilingual podcast—to explore how and

why people speak multiple languages and how it shapes their everyday lives. Some interviewees learned a second

language for professional advancement; others did so as children to engage with their immigrant parents; and still others

are expatriates who’ve picked up enough words and phrases to get by. One of the book’s main objectives is encouraging

English-speaking American readers to expand their horizons. It also gets into the history of linguistic trends in the United

States, including the phenomenon of English-only advocacy. Leveen’s writing is solid, and he does an excellent job of

weaving his many discussions into an overarching narrative; the compelling stories keep the pages turning despite the

book’s considerable length. He’s realistic about the challenges of learning a new language but still encouraging (“I’ve

never heard anyone say to me, ‘I took four years of high school band’ and then complain that they can’t sit in with the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra”), and he urges readers to understand bilingualism as a continuum, not a binary status.

Appendices provide additional references for those interested in bilingualism advocacy, and a substantial collection of

endnotes provides additional discussion.

A well-written, attention-grabbing journey into polyglot life.

When we set the US norm of monolingual English education, it was early in the twentieth century. Then we were aligned with the science of the day, and the focus on English-only education was a practical thing to do in order to build the greatest system of free, public education the world had ever seen. Today, what we know about the benefits of bilingualism has dramatically changed. The lead we once enjoyed in education has vanished, and we’ve been surpassed by nations that encourage bilingual education. Knowing what we know today about the mental health benefits of bilingualism—benefits that can last throughout a lifetime, even to delaying the symptoms of dementia—should we see a bilingual education as a matter of public health?

Many of the successful practices American adults have seized upon are just as relevant for children, such as the importance of doing what you love in the language, and the unimportance of correcting speech. And while it’s never too late to begin learning a language, it’s never too early, either. The earlier children emerge as bilinguals, the more years they have to benefit from the many blessings that being bilingual confers.

When you adopt a language, it means you take the long view. It relieves you of the pressure to believe you’re going to be anything close to perfect for years to come. And that’s fine. You can still enjoy the hell out of the process of getting there—which is sometimes fast and easy, and sometimes slow and hard. You might fail at remembering a word ten times. Just laugh and keep going. Remember: adopting a language is a lifetime commitment. We’re all going to have our off days.

Scientists have shown bilingualism to be brain-changing. It can also be life-changing.

In America’s Bilingual Century, author Steve Leveen takes you on a journey of reinvention—of yourself, your children, and the country—that takes place when we embrace bilingualism.

You’ll find in this book both practical advice and artful wisdom.

For adults who’ve never mastered a second language and believe they never can, Steve debunks myths, reveals the good news on improved teaching methods, and shares some of the learning techniques that work well for adults.

For parents, he shows the decisive advantage that bilingual children have—not just in language class, but with all their learning. He also takes parents on a cross-country tour of dual language immersion programs, which may well be the future of education in America.

For every American, he takes us back into our history, exploring why a country that contained many languages at various periods is ready to be that country again…but better. Then he re-imagines for us how an America of flourishing bilingualism might look, sound, and feel.

Is bilingualism in our country’s future? Is it in yours? It just might be after reading this thought-provoking, eloquent, and heartwarming book by an aspiring American bilingual.

No matter what your prior experiences in language learning— even if you think you’re inept at languages, even if you had a terrible experience in junior high—you can become bilingual and experience the joy that comes with entering another world and living another life. You can help your children and others in your family do the same. And finally, you can help our country, one citizen at a time, become more knowledgeable of the world, and more respected in it.

Rob Kennedy, Susan Erickson, Rick Griswold, Alejandro Capriles, Karla Hernandez, Martha Leon, Jon Paricien, Jose Colon

Founded in 2013, Daruma Tech is headquartered in south Florida, the third largest Spanish-speaking area of the United States. The staff frequently works with clients who need to reach a multilingual audience, developing multi-language websites and mobile apps. Staff members manage the translation, localization and implementation of content. Staff members themselves speak a multitude of languages. “It creates an interesting multicultural environment where you are always learning something new about language, people and cultures,” says Susan. (The word daruma, by the way, is Japanese for a doll that is a traditional symbol of resilience.)

Alejandro, Karla, Martha, and Jose are native Spanish speakers with English as a second language. Rob has an elementary proficiency in French.

Rob: “I was able to use my student French when bicycling through France and French North Africa. Although my French was terrible, the French have a soft spot for bicyclists and were most gracious.”

Alejandro: “When I was 7, I came to the United States from Venezuela to attend a baseball camp in Boca Raton. I remember feeling really nervous because I couldn’t understand a word the other kids were saying. One day after training, the kids were begging the coaches to throw fly-balls at us that we would have to catch. We were competing and teasing each other (I still couldn’t speak English, but I guess they understood my excitement and body language). I remember they were all yelling, ‘One more! One more!’ and then the coaches would throw another fly-ball at them. After watching this for a few minutes, I understood what it meant, so I started asking for ‘One more!’ as well. That was the first time I was able to convey something I wanted to say in English. After spending about a month in that baseball camp, I learned a lot of basic words and sentences, and when I came back home, my English classes were easier. I also started watching TV shows in English all the time, and by the time I permanently moved to the States, I was fluent. Being able to speak a second language is one of the things I am most proud of.”

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Caroline was a force in the world of IBM, becoming the youngest product manager for the IBM PC in its South Africa division, and later, a Senior Marketing Representative for IBM in Boston.

But the entrepreneurial itch was there. She created a highly successful retail destination in Marblehead, Mass., both in store and online. She’s also an independent publisher who uses her considerable social media skills to promote authors’ books.

A killer ear for Afrikaans, after living in South Africa

“When I was 15, my family welcomed a French girl my age into our home in England for several months. Naturally, we became friends, and I was happy to coach her in her English. ‘Why don’t you come home with me to France and meet my family?’ she suggested when school ended.

“I was, of course, delighted. I’d taken some French at school and was sure that between what I’d learned and my friend’s facility with English, I would have no trouble communicating.

“But the minute we alighted from the ferry in Calais, my friend announced—in French—that there would be no more English spoken while we were in France. And so my unplanned immersion into the language began, very different from the toe in the water I had anticipated.

“At dinner, her father would ask me, in French, my opinion on Watergate (this was the 1970s). I barely had one in English—it was not the kind of thing teenaged girls bothered about—and I certainly didn’t have one in French. And even if I did, I quickly discovered that my schoolgirl French was woefully inadequate for real-life conversations.

“One day, a friend around our age came to visit. He was French, and was learning English. He and I talked—in English—for a while, and finally he said to me, ‘What’s “sukee”?’

“I had no idea, I assured him.

“‘Yes, you do,’ he insisted. ‘You’ve been saying it all afternoon.’

“Sukee? He must be thinking of some other word. But I had barely finished responding to him when he pounced. ‘There! You’ve just said it again.’

“What on earth had I said? And then I got it. Sukee was how his French ears heard my English pronunciation of ‘it’s okay.’

“Had I not been struggling to understand my French family’s conversations, spoken the way we all tend to in our native language—quickly, sliding together consonants and vowels—I might have wondered why this young man couldn’t grasp such a simple word. But my immersion baptism had taught me that what we learn in classes and the way people really talk can be far different. But sukee: eventually our ears start hearing in the language.”

Fernando’s life work began well before he graduated in 2008 from the Western Institute for Technology and Higher Education in his hometown of Guadalajara, Mexico, with a communications degree. By then he had already started a media observatory blog that monitored the agendas of print and electronic media; created TV segments for broadcast during the 2006 Germany World Cup; founded the first internet radio station at his university; and co-founded the NGO Ciudad para Todos (A City for All), which champions pedestrian-scale urban environments. Since then, he has collaborated with close to a dozen media outlets, become an award-winning storyteller, and is an ongoing contributor to NPR’s Latino USA.

In addition to producing and co-writing with Steve the America the Bilingual podcasts, Fernando has created a second storytelling podcast, Esto no es radio (“This isn’t radio”). He is also a contributor to KCRW, a Los Angeles radio station.

Fully bilingual since he was 16, Spanish and English. “The tipping point came when I enrolled in a bilingual high school, where all the subjects were taught in English.”

“In my parents’ library in Guadalajara, there was a box containing a self-guided course on how to learn English. I don’t think my parents ever opened it. How could they? My dad had to work in the mornings and study accounting in the afternoons. My mom had to do almost the same. At the end of the day, there was no bandwidth in them to learn another language. So their English got stuck at shopping level. When my parents came to visit me last year in California, I knew my dad wanted to practice his English. He’s now retired. He wants to go beyond shopping level: he wants to understand. So for the rest of his stay, I would have some conversations in English with him. He would beam every time he got his point across. I thought of him before the release of the first America the Bilingual podcast. He and Steve are both recovering monolinguals. They’re the same age. They could be friends, talking about music and the best dichos. Think of all the friendship possibilities that speaking in another language provides. It’s not the recipe for world peace. But it’s definitely one of the ingredients toward understanding one another. And with this bridge of sound called America the Bilingual, we’re going to do our part.”

Adults can also learn languages, and in some ways, better than can children.

Today’s adults have never had better conditions for language learning—classroom teaching is better; technology makes learning more game-like; we can watch movies, listen to music, read newspapers, magazines and books in world languages with ease. It’s easier to travel to other countries—both for real, and virtually.

With rapidly improving artificial intelligence, we are entering a golden age of language learning.

Mim is the author of three books on the English language and three micro-biographies of John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy and Eleanor Roosevelt (both women were multilingual). She has published specialty books for the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, the Folger Shakespeare Library and other leading cultural institutions that have included books in Spanish, Italian and Latin. She also edited and produced Steve’s first two books.

For the MacArthur Foundation, she was a principal designer of ¡Triunfo!, a multimedia fundraising gala for the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce of Palm Beach County. In addition, she has developed a line of bilingual “brain games,” including Spanish-English crosswords, a 10-language dice game and a five-language set of children’s blocks. She has also been a guest blogger for the translation site Smartling.

Studied Latin for two years and French for four. To live the journey of America the Bilingual, she is learning Spanish.

“The year I lived in northern England, with its figgy-pudding-rich dialects, I spent the first couple months going to all sorts of places I never planned on. When the bus driver would ask did I want to go to X, Y and Z, loov, I would smile and say yes. I had no clue what he was saying. But it piqued a lifelong curiosity about languages. With my smattering of French and, more important, the Latin that had been drilled into me in school, I managed to muddle my way through much of western Europe and make some sense of the languages. Until, that is, I went to Cymru. Not one bit of Romance-language underpinnings helped me know that Mae’n dda gen i gwrdd â chi meant ‘Pleased to meet you.’ I was completely bethumped—but also beguiled by how utterly different the language was. For me, America the Bilingual is a chance to (hopefully) become conversant in another language. But it’s also a way to understand, even the tiniest bit, so many other languages and their cultures. Who knows all the wonderful places that being on the AB bus will take us? (Cymru, btw, is Wales.)

Beckie has been devoted to teaching French ever since she graduated from Boston University in 2007 with a B.S. in Modern Foreign Language Education and a B.A. in French Language and Literature. (She also holds an MAEd. in Foreign Language Education for French from Wake Forest University.) Beckie spent a year in Côte d’Ivoire designing and implementing the pilot of a French immersion program for JourneyCorps humanitarian volunteers. She currently teaches French at Lexington High School in Massachusetts.

Beckie is the Chair of the Global Engagement Initiative Committee of ACTFL, where she also sits on the advisory board of its New England branch and is a board member of its Massachusetts branch. She is a regional board member of the American Association for Teachers of French as well. Beckie is the author or co-author of numerous articles in professional publications and continuously undertakes courses at various universities to refine her skills.

Every year bar one since she was 15, Beckie has spent time in a Francophone country.

Fully bilingual, French and English. “I’ve also dabbled in Spanish.” And she can greet people in Djiula and Senefou.

“Growing up, languages were important to my family. My mother speaks French; my dad reads Latin, Greek and Italian. My older sister was great in German. So I chose French—mostly because of the food! I started studying it in high school and excelled at it; it came naturally to me. When I was 15, I went to France and loved it. The next summer I went back, speaking almost exclusively in French. I can do this, I told myself. At B.U., I quickly completed my minor in French. My dean said that if I loved French that much, I should teach it. And I do.”

If speaking naturally from actual knowledge of the same language is like hugging, speaking through machine translation is like waving from across the street.

We should use technology both for casual translations of many languages, and to help us deepen our understanding of languages and the people who speak them. Think of technology as enhancing human capabilities, rather than replacing them.

We now know that children who are supported in their heritage language skills match or exceed students who are denied the learning of their heritage languages.

But for most of the 20th century, immigrant parents commonly suppressed their heritage languages, not speaking Polish or Italian or Spanish to their children. Like all parents, they wanted their children to do better than themselves, and to not suffer the prejudice they had suffered from having imperfect English. The goal was unaccented English—and only English—as the mark of being fully American. Moreover, up until the 1960s, the “scientific” evidence supported the idea that more than one language would confuse children and hold them back in school.

Today, attitudes— both popular and scientific—have shifted. Unaccented and perfect English is still the goal, but added to it is the capacity to speak the family’s heritage language, and maintain important cultural connections.

From birth to the age of 5 or 6, children’s brains are wired for language learning. If Mom speaks one language, Dad another and everyone else a third, children will sort it out and in a few years be able to converse in all three.

Even with a monolingual beginning, once school-age, children respond well to dual-language schools where they are taught in two languages. The number of dual-language schools producing bilingual and biliterate students is growing. More states are recognizing high-school graduates for achieving biliteracy with a Seal of Biliteracy on their diplomas.

Bilingualism is a gift we know how to give.

While the ability to speak one another’s languages is no formula for peace (as civil wars readily testify), the process of learning the language of another group is inherently pacifying.

Language learners can’t help but learn another culture while learning a language, and when you know more about a culture, it’s common to come to admire, and even love, aspects of it. What’s more, when language learners practice with people from another language group, they learn about one another, they break down prejudices, they often become friends.

It is the process of language learning even more than the end result—the journey rather than the destination—that leads to more peace in the world.

Does the whole world speak English? Not quite, not even in France, if you really want to do business. Meet Ben Macklowe, a New York City kid, who grew up as a monolingual English speaker, until he messed up big time and then took matters into his own hands. Now he’s passing The Gift on to his baby boys. The following 14 minutes may light your path…

Graphic designer, art director, creative director: these titles and a few more have been Carlos’s, who is currently the creative director of the Carlos Plaza Design Studio in Hollywood, Florida. He is a graduate of the Design Institute of Caracas and the former publisher and art director of that City’s Estilo Magazine. Carlos lived in a number of Latin American and European cities before landing in South Florida. He has put his artistic stamp on the collateral of many companies here—magazines and media groups, cruise ship lines, a high-end retailer. One of Carlos’s longest tenures has been with American Media (AMI) Specialty Publications, where he was both creative and art director.

Design is more than just a skill that Carlos excels at; it’s something he lives 24/7. While working his day jobs, for example, Carlos also spent seven years as the director of the Native Florida Gallery of art, which he founded. His affinity for the visual arts and in particular, for fine-arts photography (which he learned as a teenager from his father), is much of the reason for his sophisticated eye as a graphic designer.

Fully bilingual by the age of 17, Spanish and English. Fluent in Italian—“my mother tells me that I was completely fluent until I was about 7 years old, when my father moved me from an Italian high school in Venezuela to a Catholic one, where Spanish was the primary language and English the second.” Carlos also studied German during the four years he lived in Vienna.

“When I was hired as the design director of Boca Raton Magazine in 1994, I was at one of my first staff meetings and trying to settle an argument between sales and editorial. I told everybody that I wasn’t taking sides with one or the other—I was just being the devil’s avocado. Everybody broke up laughing. This was the last time I confused the English words of ‘avocado’ and ‘advocate,’ but it earned me a nickname among some of my close friends.”

Leave A Comment