Don’t Believe You Aren’t Good at Languages!

Have you heard the same thing I’ve heard when adults describe the language classes they took in school? What I’ve heard again and again goes something like this: “I took four years of French and can’t hold a conversation!”

The number of years of classes will vary, as will the language, but the feeling of frustration is constant. And no wonder. After so much effort taking classes, people expect to be able to have a conversation.

But at the root of this common frustration is a misapprehension, widely shared, that being able to speak reasonably well in another language should take a few hundred hours. The truth is, it takes thousands of hours. And not just in classes that may focus on reading and answering multiple-choice test questions, but in thousands of hours of speaking and listening.

Why we have this misapprehension is perplexing. Most people don’t expect, after four years of high school band, to be able to sit down and play with a professional group. Perhaps it’s because we already have conversations all the time in our native language, and see other people doing the same with their native language, that we think, how hard can it be?

There’s a name for this miscalculation. It’s called planning fallacy, a well-known cognitive bias that describes our common habit of badly underestimating the time to accomplish almost anything difficult. But that doesn’t make it any less frustrating for the millions of aspiring bilinguals who feel the sting of disappointment.

When diplomats must prepare themselves for professional work in another country, this planning fallacy doesn’t exist. In the US State Department, for example, when staff members are assigned overseas, assuming the staff member is a beginner in that country’s language, they go to school full time for a year, racking up a couple thousand hours of language use at the direction of skilled instructors.

Even that’s not enough to achieve more than a working proficiency. And that is for relatively easy languages for English speakers to pick up, such as French, Spanish and German. For difficult languages, including Arabic, Korean, Japanese and Mandarin, it’s more like two years.

Because of this widespread underestimate of the time required, millions of Americans conclude, erroneously, that they “just aren’t good at languages.” I’ve been told that so many times by well-educated, accomplished people that I get irritated. I ask them, “Well, how good are you at English?”

That gets a perplexed look and usually a hesitating reply of “Pretty good, I guess.”

“You’re not pretty good,” I retort, “you’re fluent in English and could be fluent in another language, too. It’s mainly a question of time.”

People usually nod at what I’m saying, but without a lot of conviction. After all, it’s kind of abstract—the difference between hundreds of hours and thousands of hours. Logically, we know it’s 10 times more hours, but still, it’s hard to wrap our heads around what that means.

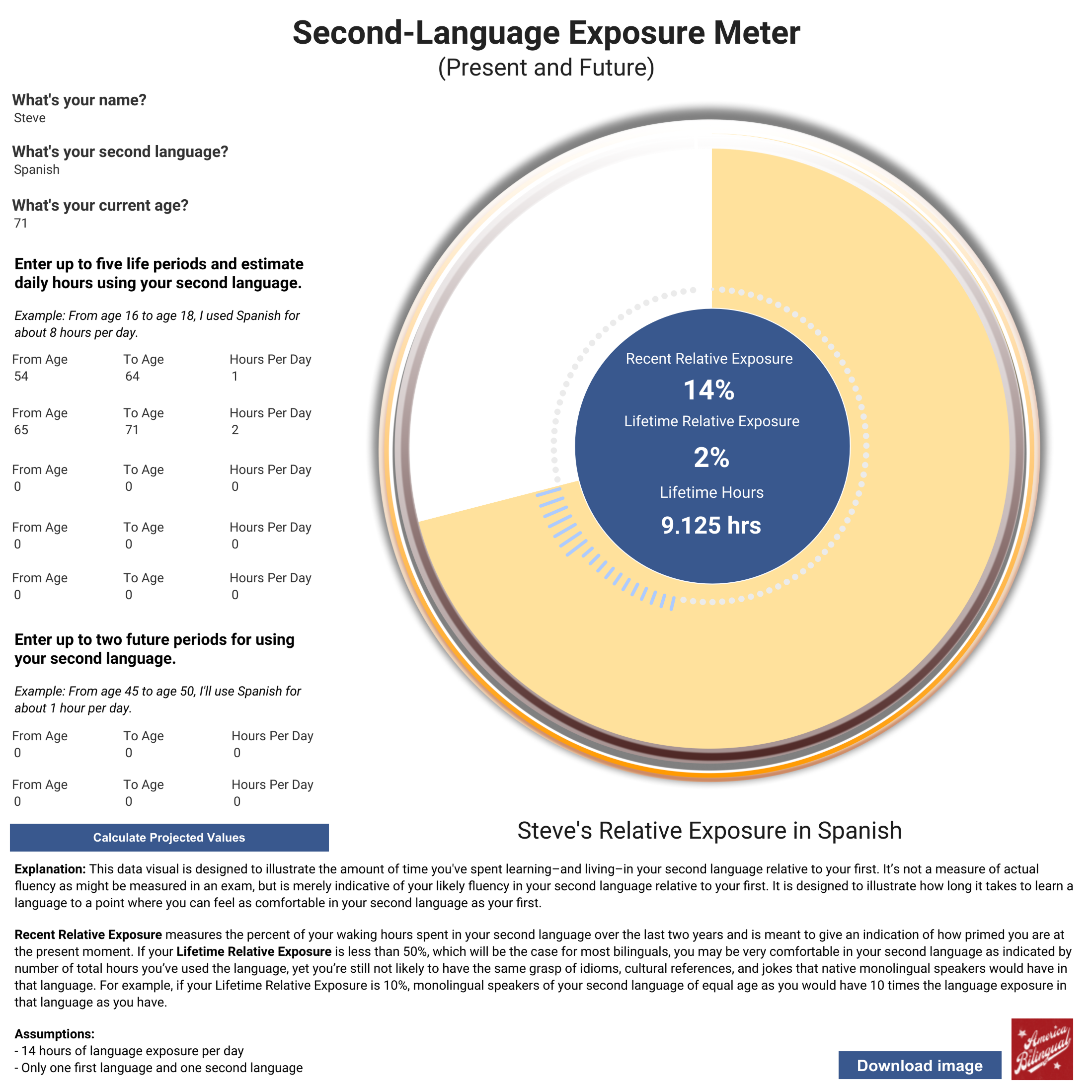

And so, in an effort to help language learners understand how many hours they have devoted to their second language, and how this compares with the hours accumulated in their native language, we have developed the interactive data visual you see here. This is a beta version that we hope you’ll try and offer us some feedback.

Getting some perspective

I’ve estimated my own time devoted to using my adopted Spanish over the years so you can see an example.

In my case, I didn’t start learning Spanish until midlife—age 54, actually. I’ve been pretty diligent over the years, especially in recent years when I moved from 1 hour per day to twice that, on average. That’s hours of using the language—either speaking, reading, listening or writing. (It also includes time studying, but these days I’m using the language more than studying how to use it.)

As a result, I’ve accumulated more than 9,000 hours of exposure to Spanish. (I’ve set the language on all my devices to Spanish, which is why the number displays as 9.125.)

My 9,000 hours have given me enough command of Spanish to have reasonable conversations with native speakers (assuming they have a sense of humor). I’ll still make grammatical errors and struggle for vocabulary, but I can work around those things and get the ball over the net. What’s more, I love speaking now, and seek out chances not just to speak, but to text, write emails, read, watch movies, etc. My Spanish language skills are a source of great joy and fulfillment in my life.

And yet…

Observe the percentages of my Spanish language exposure compared with my English exposure. Recently (in the last two years) I’ve been using Spanish a great deal and thus my Spanish is pretty fresh. I feel primed to use it. But only 14% of my recent waking hours have been doing so. For 86% of my waking hours, I’ve been using English. So when I converse with a native speaker who speaks Spanish all day, will there be a difference in my command of the language? Absolutely! I’ll be speaking with people who have 10 times, 20 times or even 40 times more usage of Spanish than I have, depending on their age.

They understand cultural references, jokes, idioms, that will confuse me. They can understand verbal shortcuts and mumbling that leaves me asking, “¿Como?” My Spanish-speaking friend will quickly realize they are speaking with a non-native and will likely slow down, use simpler sentences, and expect less from me. We can still have a meaningful conversation, and even an enjoyable one, but it will be different from the kind two native speakers will have.

Your turn: check your own stats

I encourage you to put in your own data in the live meter below. You’ll have to make some estimates, and clearly this is not a measure of your actual proficiency; rather, it’s a relative indicator of where you stand at this point in time spent in your second language relative to your first. You can also put in your plans for using your language in the future and see where that would get you, both on an absolute hours basis as well as a percentage basis. You can download and print out your personalized meter to help you set your goals.

This is only for your own information: we won’t see or collect your data.

Three takeaways

Here’s what to expect, the more time you spend bringing your second language into your life:

- You can get great at your adopted language by devoting a reasonable number of hours consistently over several years.

- You’ll likely still be far from a native speaker.

- That’s perfectly okay!

First, you can gain sufficient hours to become comfortable, to enjoy, and even to glory in your adopted language. Second, you’re still likely to be quite less able to understand and to convey your thoughts than a native speaker. Third, that’s perfectly okay!

One can say that life is too short to speak only one language, but it’s equally true that life is too long to speak only one language. Meaning that, with normal life expectancies, we have all the hours required to become a comfortable speaker of more than one language. We can live the life of a bilingual and enjoy it to the fullest.

Each of us is awake about 5,000 hours per year. And when we’re awake, we’re usually using language in some way. That’s enough time, if you commit an hour or more every day, to get comfortable.

Persistence and your accumulated skills are what pay off in the long run—like compound interest.

Persistence is power

I hope you won’t fall into the trap of thinking you’re just not good at languages. Put in the time and you’ll speak your second language with as much enjoyment as you do your first—if not quite with the same skill.

Daily persistence is why we like the term “adopted language” to describe this second language you have committed yourself to. Use your adopted language every day and eventually you’ll be bilingual. It’s what we’re all meant to be, and it’s one of life’s great pleasures to fulfill our potential.

Your feedback, please

Let me know how you fared with this beta version of the data visualization. How could we improve on it? Email Steve@AmericatheBilingual.com. ¡Gracias!

—Steve Leveen, Founder, America the Bilingual Project

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

Leave A Comment