44. Africa’s Relaxed Multilingualism

In the west African country of Cameroon, it’s not unusual for youngsters playing a neighborhood game of soccer to encounter different languages among their friends. And throughout Africa, it’s not uncommon for people to speak three languages—even if they don’t write or read all three. How do they do it? And what can the United States learn from this continent of polyglots?

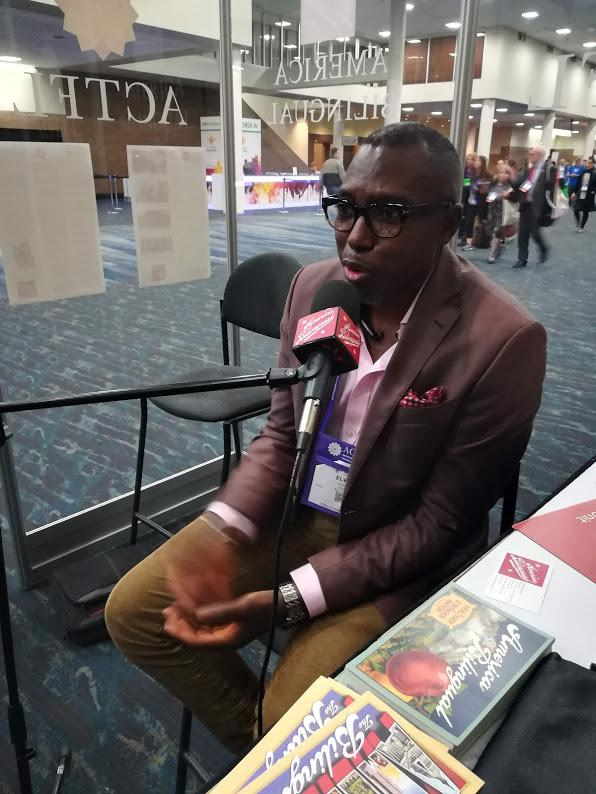

For Episode 44 of the America the Bilingual podcast, Steve talked with three African educators he met at the 2018 ACTFL conference. All these gentlemen are teaching global languages to students here in the U.S. Two of them—Martin Fameni and Elvis Etah—teach high school students, Martin in Virginia and Elvis in Mississippi.

Both Martin and Elvis are from Cameroon, both speak at least two Cameroonian languages in addition to English, and both teach yet another language: French. They are also representative of the way Africans bring different languages into their lives.

A newspaper stand in Tanzania.

(Photo by Adam Jones, Ph.D. – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27892534)

Practical Polyglots

In Africa, people approach multilingualism pragmatically.

Martin explains how it works for most young people: “They start with their dialect [those soccer-field languages], then they learn whatever is the primary language of that country, and then they learn another language in school.” Often the language in school is a European one that speaks to an earlier era of colonial rule—French, Portuguese (to a lesser extent), or English.

“If you lead your life among people who speak different languages, you have a reason to learn them—and opportunities for practice,” writes the language researcher Gaston Dorren in his book Babel: Around the World in Twenty Languages, about Africans’ success with languages. Multilinguals, in other words, beget multilinguals.

A myriad of languages are spoken in Africa. Geofred Osoro, the third educator Steve spoke with, puts the number at 2,000. Geofred teaches the continent’s dominant language, Swahili, at Wellesley College in Massachusetts.

Geofred’s trilingualism is emblematic of how Africans use different languages in different ways—for local identity, national identity, and international communication. He speaks his local language of Kissi, from the part of Africa where he was born; plus Swahili, the language of Kenya in eastern Africa, where he lives; and English, “the language of education,” as he describes it.

It’s a practical approach that, for the most part, works. Babel’s Dorren describes it as a “connection between necessity, opportunity and achievement.”

Martin Fameni Elvis Etah Geofred Osoro

From Transactional to Treasured

But these are languages, so more than practicality comes into play. Languages, after all, are not merely transactional. They speak to culture, traditions, memories. They are something to keep and to treasure.

This is particularly true when it comes to protecting the continent’s native languages. As Geofred says, “People have to know their language. You have to get into their mind, what they speak, in order to know what they think about—their worldview, the way their construct their reality, which is found in their languages.”

The many flags of Africa suggest the many languages of Africans—approximately 2,000.

AN AMERICAN POSTSCRIPT

There is one place in America where a community of people speak in a way that echoes this linguistic elasticity: the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor of the southeastern United States. Stretching from approximately Wilmington, North Carolina, south to Jacksonville, Florida, and encompassing the coast as well as the islands off of it, the area is home to the Gullah people, who speak the language of the same name.

The Gullahs are descendants of the captive West Africans who were brought to the United States in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, often to work the profitable rice plantations of South Carolina. Many were from Sierra Leone, part of Africa’s “Rice Coast,” and unlike the European-American slaveholders, they were highly skilled in rice cultivation.

They carried little with them but this knowledge…and a language that was a mix of numerous African languages plus Elizabethan English. Gullah is a Creole, a way for people of many languages to speak a common one. For Gullah, these languages include Yoruba, Mandinka, Igbo, Mende, and many others spoken in Africa.

There is an old Mende proverb: “You know who a person is by the language he cries in.” In Gullah can be heard the tears of many African languages, preserved in a unique way on a continent far from their origins.

Recommended reading

Gaston Dorren’s Babel: Around the World in Twenty Languages, which you’ll hear about in the podcast, offers a lively, informed assessment of the planet’s most-spoken languages. The chapters focus on a specific aspect of each language, which makes this complex topic manageable. And, the author promises, if you gain proficiency in just four of these languages, you’ll be able to go almost anywhere on earth and be prepared to talk.

Gullah Culture in America, by Wilbur Cross, takes readers on the journey from Sierra Leone to the southeastern coast and islands of the United States, where African speakers of Gullah have maintained their Creole language—and thus their culture—for centuries, despite nearly insurmountable odds.

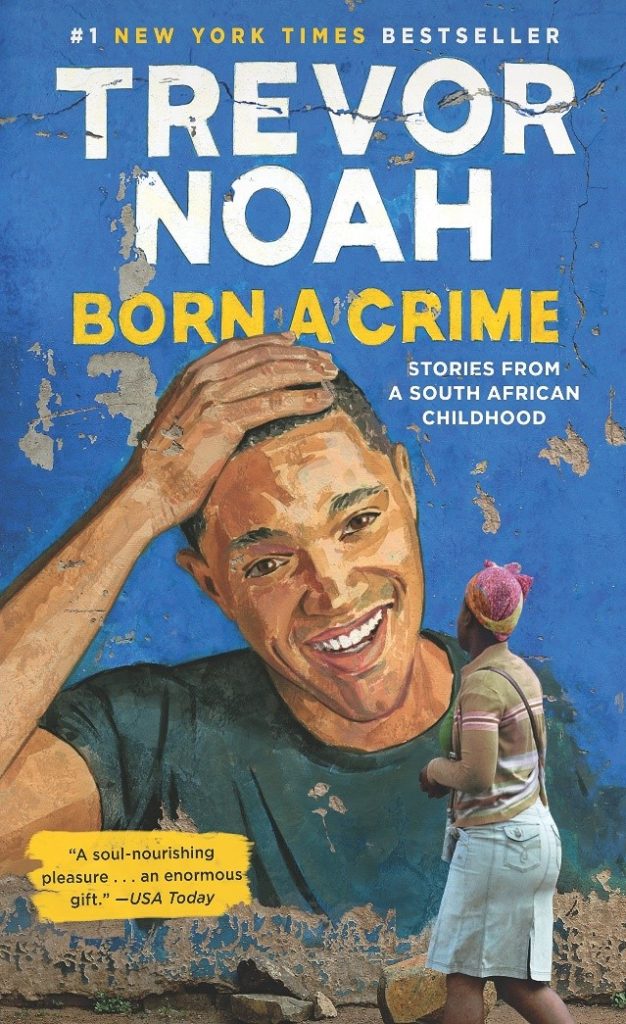

In Born a Crime, Trevor Noah’s memoir of growing up in apartheid South Africa as the child of a black mother and white father, he recounts how his mother taught him multiple languages to bridge all kinds of social divides. He learns English but speaks Xhosa at home. He also learns Zulu, Sotho, Afrikaans and the native language of his father: German.

HEAR THE STORY

Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes. Or on SoundCloud here. Steve comments on Twitter as well.

Credits

The America the Bilingual podcast is part of the Lead with Languages campaign of ACTFL—The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

This episode was written by Mim Harrison, the editorial and brand director of the America the Bilingual project, and edited by Fernando Hernández, who also does the sound design and mixing. Steve Leveen is the executive producer and host. Our social media maestro is Caroline Doughty. Beckie Rankin is the podcast’s associate producer. The team at Daruma Tech powers our website. Graphic arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio. Meet the America the Bilingual team—including our bark-lingual mascot, Chet—here.

Support for the America the Bilingual project comes from the Levenger Foundation.

Music in this episode, “Quasi Motion” by Kevin MacLeod, was used with a Creative Commons Attribution License. Our thanks to Epidemic Sound for helping us make beautiful music together.

Let us know what you think

If you like this episode, please share with a friend and subscribe on iTunes, or wherever you listen to podcasts. And let us know what you think: leave a comment on our Facebook page about this episode, or on any other thoughts you have about bilingualism in America. We love hearing from our listeners!

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).