40: Children of a Silent God: A Bilingual Journey Through American Sign Language

While bilingual schools for spoken languages are becoming more popular in America, fewer children are attending bilingual schools for signed languages. What does that mean for deaf children who should be learning ASL—American Sign Language—as their first language, and at a young age? And what, if anything, can reverse the trend?

In this episode, we talk with two professionals from Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., the world’s leading university for the deaf; an attorney for education policy at the National Association of the Deaf; and a college student who is making deaf education her lifelong mission. What are the consequences for young deaf students in America who are not taught their school subjects in both ASL and English?

Young age matters

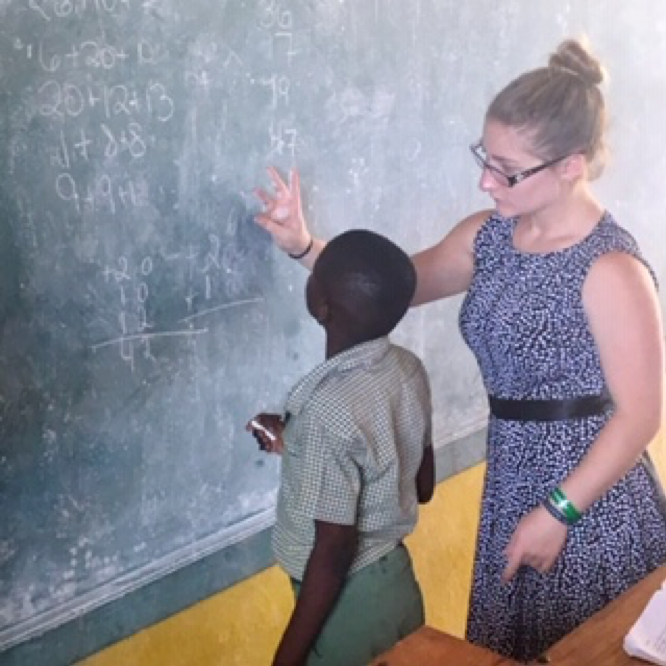

Sierra Weiner was all set to make a career in biotechnology…until she took an ASL course at her high school, Seminole Ridge in South Florida, and was hooked. She’s now studying ASL for interpreters and deaf education at the University of North Florida. She got her first taste of teaching young deaf people to sign when she was part of a deaf-education program in Haiti after her freshman year.

A 13-year-old boy she worked with was emblematic of a problem that many deaf children confront when ASL has not been a significant aspect of their education from a young age.

“He was quite a few grades lower than what he should have been, which is very common for the deaf in Haiti as well as America,” says Sierra. “And it’s pretty much universal.”

With the number of deaf children in America enrolled in bilingual ASL-English schools declining, the fallout from that follows the students throughout their academic career. Students admitted to Gallaudet can attend remedial classes to help them improve their signing skills.

“But I think that in some ways they have a difficult adjustment to make being on this campus, where they need to sign all the time,” says Ivey Wallace, the recently retired director of Gallaudet University Press.

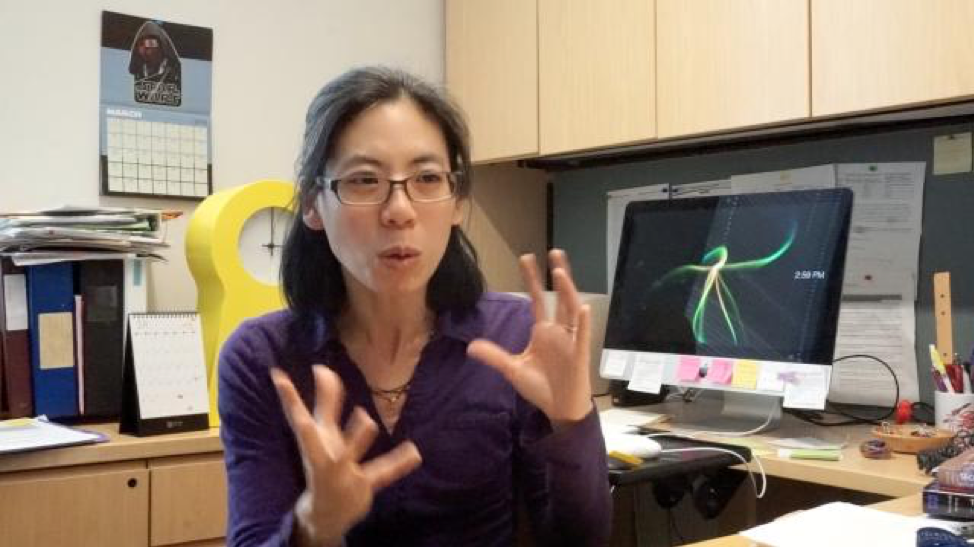

The signing culture is embedded into Gallaudet’s bones, and even its buildings. “There’s a lot of glass here on campus because it’s a visual campus,” says Debbie Chen Pichler, a professor of linguistics at Gallaudet.

Ivey Wallace – Retired Director, Gallaudet University Press

It’s more than lonely being the only

“There are many repercussions, many disadvantages that you suffer when you are exposed to your first language late, and that’s still a majority” of deaf children, says Debbie.

“The trend has been for states and local school districts to place deaf and hard-of-hearing students in public schools with little to no support or access in sign language,” writes Tawny Holmes Hlibok, Education Policy Counsel at the National Association of the Deaf.

Being the only deaf child in the school is not a good thing. As Tawny writes, “It has a marked social-emotional impact which we are only starting to measure.” Research shows that deaf children need just the opposite of this, she says, namely “language-rich environments such as ASL/English classes, including direct access to peers and teachers using sign language.”

Tawny Holmes Hlibok – Education Policy Counsel, National Association of the Deaf

Debbie Chen Pichler – Professor of Linguistics, Gallaudet University

Opening our eyes to a world beyond hearing

In interviewing our guests for this podcast, all of whom are passionate advocates for making deaf children some of the earliest bilinguals (you can teach ASL even to infants, as we discovered in Episode 29, Steve and I found ourselves once again realizing how much we don’t know about deaf culture.

Sierra summed it up well. She told Steve: “There is so much more than just this hearing world that we live in.”

We thought we would share with you some insights about ASL that we learned from our guests, in addition to what you’ll hear in the podcast.

- ASL is one of just many sign languages

“Every country has its own sign language,” say Ivey. Some have more than one, adds Debbie, and there are similarities among the various languages. “That’s probably largely responsible for why deaf people seem to be so good at learning a second sign language,” she adds.

- The “deaf dinner-party paradox”

The commonalities among all these sign languages make it easier for a room full of deaf people who sign in all different languages to carry on a conversation with each other—what Debbie calls the “deaf dinner party paradox.” And, she says, the group communicates on a sophisticated level—she’s witnessed it at international conferences. Try that with a room full of hearing people who all speak a different language, and the results would be—well, there wouldn’t be any results as far as true conversation. And they could be somewhat disastrous if it were a dinner party.

- Cochlear implants are not a panacea

“There’s a lot of work that has to go into helping a deaf child learn English, even if they have a cochlear implant that works,” Debbie cautions. “They don’t hear the same way that you and I hear; they hear in a way that needs to be monitored all the time. There’s a lot of calibration that goes on. Says Sierra: “A cochlear implant doesn’t solve the problem,” and she maintains that being deaf should not be viewed as a “problem.” Instead, she says, “I think it would be useful for everyone to learn American Sign Language.”

- Lip reading is far from foolproof

If you are communicating with a deaf person who is reading lips, keep in mind that it’s a challenge to correctly capture a large percentage of words. Facial expressions will help to contextualize. As for lip movements, says Debbie, “you want to make sure that the mouthing the deaf person is seeing is as natural as possible, so don’t exaggerate.”

Sierra Weiner, University of North Florida student studying ASL, teaching deaf children in Haiti

HEAR THE STORY

Listen on iTunes by clicking here: America the Bilingual by Steve Leveen on iTunes. Or on SoundCloud here. Steve comments on Twitter as well.

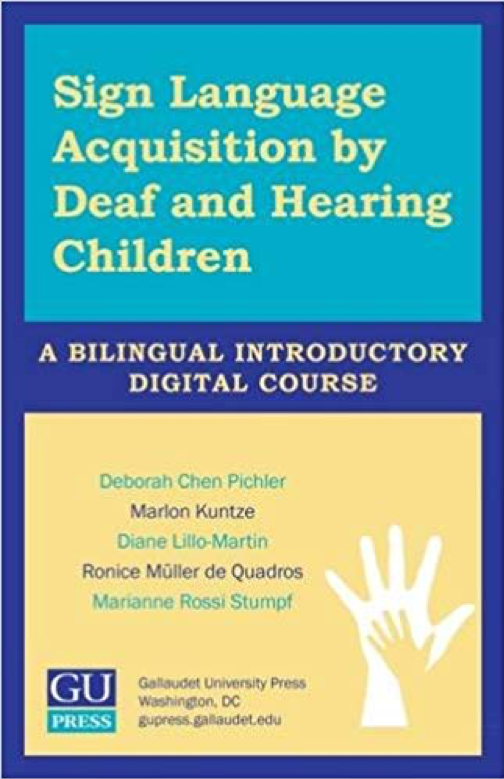

Recommended reading and watching from Gallaudet

To read:

To watch:

For an overview of sign language acquisition that’s also presented in ASL with English voiceover, watch this webcast from the Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center at Gallaudet.

About the episode title

As you probably guessed, the title of this episode was inspired by “Children of a Lesser God,” which has been both a movie and a play. It’s a poignant, and at times troubling, look at the different worlds inhabited by those who hear and those who do not.

Credits

Special thanks to Howard Rosenblum, CEO of the National Association of the Deaf.

The America the Bilingual podcast is part of the Lead with Languages campaign of ACTFL — The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.

This episode was written by Mim Harrison, the editorial and brand director of the America the Bilingual project, and edited by Fernando Hernández, who also does the sound design and mixing. Steve Leveen is the executive producer and host. The associate producer is Beckie Rankin. Rob Kennedy, Alejandro Capriles and the rest of the team at Daruma Tech power our website. Graphic arts are created by Carlos Plaza Design Studio. Caroline Doughty is our social media maestro. Meet the America the Bilingual team—including our bark-lingual mascot, Chet—here.

For a transcript of this podcast, contact us at americathebilingual.com.

Support for the America the Bilingual project comes from the Levenger Foundation.

Music in this episode, “Quasi Motion” by Kevin MacLeod, was used with a Creative Commons Attribution License. Our thanks to Epidemic Sound for helping us make beautiful music together.

You can book Steve for many different audiences

You can book Steve for many different audiences

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).

First, know that she has one of those glorious English accents (or what all of us who are not English would call an accent), which makes her a natural for the audio book narration that she does. Although U.S. born, Caroline grew up in England and studied literature at the University of Warwick (fyi for American ears: that second “w” is silent).